History of tapestries in Western Europe

Very little is known about the origins and the early history of tapestry weaving. Textile fragments are sporadically found during archaeological excavations because the fabric eventually disintegrates and does not survive underground, unlike, for example, ceramic objects.

However, we do know that objects had been manufactured in the tapestry technique in Ancient Egypt around a thousand years before Christ. We also know of specimens from the Incas in Peru dating as far back as three hundred years before Christ. The technique was also used very early on in China and Greece.

In Western Europe, we find the first traces of tapestry weaves dating back to the early thirteenth century, notably in Scandinavia and Germany. It is surmised that the technique was brought here from the East by the crusaders.

There are reports of tapestry weavers working in Paris as early as 1258, but the history of French and Flemish tapestry weaving does not really start until the early fourteenth century with Paris as the main centre. This continued until the French capital fell into English hands in 1415 during the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453). The weaving workshops closed, and many weavers were forced to flee.

In Flanders (hereafter referred to as the Southern Netherlands) at that time, tapestry production was greatly stimulated by the Court of Burgundy. The Burgundian Court’s example of frequently using series of tapestries was emulated throughout the European courts. (Fig. 1)

Around 1350, Atrecht, or Arras, then part of the Southern Netherlands, but now situated in France, became second only to Paris as the most important centre for tapestries. After the English invasion in Paris, Arras even assumed the leading position, while Doornik, or Tournai, became the second most important centre for tapestry weaving. Circa 1450, however, Tournai received the most important tapestry commissions, particularly from the Burgundian Court.

In 1477, political developments once again determined the history of tapestry production. Arras was taken by the French king and the city was completely destroyed. The weavers were also forced to flee and shortly thereafter, tapestry production in Tournai ceased. The weavers from Arras and Tournai sought refuge elsewhere. Many ended up mainly in Brussels, which, with their help, became the most important centre for tapestry manufacturing from the late fifteenth century onward.

Fig. 1

wandtapijtweverij van Anoniem Southern Netherlands (hist. region) 1495-1525 naar ontwerp van Anoniem Southern Netherlands (hist. region) 1495-1525

Millefleurs met tafereel met edellieden tijdens de jacht en herders, 1495-1525

Amersfoort, Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, inv./cat.nr. NK 3036

The sixteenth century

From around 1500, the workshops in Brussels of Pieter and Willem de Pannemaker and of Pieter van Aelst became renowned. Many large and valuable tapestry series were woven here, which in addition to wool, often also included a considerable amount of gold and silver thread. Between 1515 and 1520, Pieter van Aelst’s workshop produced a series of tapestries, commissioned by Pope Leo X, featuring the Acts of the Apostles after designs by renowned Italian painter Raphael to be hung in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican in Rome. (Fig. 2)

The Acts of the Apostles series forms an important break in the history of tapestries in several ways. In fact, this marks a significant departure from previous practices. This series is therefore regarded as the first example of tapestries in which the art of the Renaissance is expressed. An emphasis is placed on a unity of time and place in the depiction. The image is also rendered as realistically as possible, as if it were a painting. This contrasts with medieval tapestries, which almost always featured several scenes from the story juxtaposed.

The painterly principle of suggesting depth through the rules of perspective is also applied in the weave using fine yarns and a seemingly endless range of yarn shades, with stunning results.

This method is based on a full-sized example, painted in extreme detail, known as the cartoon. This greatly reduces the weaver’s input in interpreting the representation, in contrast with the tradition in the fifteenth century, when weavers often largely determined the depiction, sometimes aided by examples from other tapestries, prints or miniatures.

Thanks to their innovative nature, the tapestries after Raphael’s designs, most notably the series of the Acts of the Apostles, had an enormous influence on the tapestries woven in the Southern Netherlands after 1520.

In imitation of the series of the Acts of the Apostles, amongst other things, tapestry borders became much wider and more elaborate. In addition to decorations featuring flowers and fruit, animals and sometimes even narrative scenes were included in the borders.

Fig. 2

wandtapijtweverij van Peter van Aelst van Edingen naar Rafaël

De wonderbaarlijke visvangst, ca. 1516-1519

Rome, Musei Vaticani, inv./cat.nr. 43867

From 1528, it became compulsory in Brussels to weave the city mark into the selvage. The weaver often also included his personal weaver’s mark or signature. (Fig. 3) In the production centres outside Brussels, tapestries were generally of a slightly less fine quality, namely woven with four or five warp threads per centimetre, as opposed to about eights warp threads in Brussels. The colour palette was also more limited, featuring mainly yellow, green and blue and rarely any red. Moreover, the tapestries made in provincial regions such as Oudenaarde, Geraardsbergen and Enghien often resembled each other. The presence of city trademarks and weavers’ marks on certain tapestries shows that the cities and often also the workshops here applied their own types of borders, which facilitates attributions to certain centres.

Although the Southern Netherlands were the most important to the tapestry production in the sixteenth century, tapestries were, at the time, also manufactured in other European countries, such as France and Italy, albeit on a smaller scale.

The history of the production of tapestries in the Northern Netherlands, the region we now know as the Netherlands, begins around 1550. In the last quarter of the sixteenth century, the revolt against Spanish rule caused many to immigrate from the Southern Netherlands. Many religious, political and economic refugees settled in the Northern Netherlands. They included several tapestry weavers who established various weaving workshops, most notably in Delft and Gouda.

Fig. 3

The ciy mark of Brussels

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

In the seventeenth century, Brussels was still the most important production centre of the Southern Netherlands. In addition, tapestries were manufactured in Antwerp, while Bruges also produced some fine series.

Around 1620, a century after Raphael’s innovations, the work by the painter Peter Paul Rubens, which was mostly executed in Brussels weaving workshops but also in other production centres, marked the next major turning point in the history of tapestry. For example, the oil paint colours used by Rubens in his painted designs and cartoons became the starting point for the depictions on the tapestries. This brought tapestries ever closer to painting. From then on, the significance of a tapestry would increasingly be determined by the artist who had created the design.

Meanwhile, Rubens and other leading painters in the Southern Netherlands sought ways in which to give new meaning to the role of tapestries as wall decoration. One solution that Rubens came up with was to place the representation on a tapestry that was held up by angelic figures within the actual tapestry. He developed this idea in the extensive series of twenty tapestries of the Triumph of the Eucharist from 1625-1627, intended for the convent of the Descalzas Reales (the Discalced Clares) in Madrid. In this series, Rubens’ baroque visual language is also perfectly conveyed, with compositions featuring large figures striking dynamic and dramatic poses. (Fig. 4)

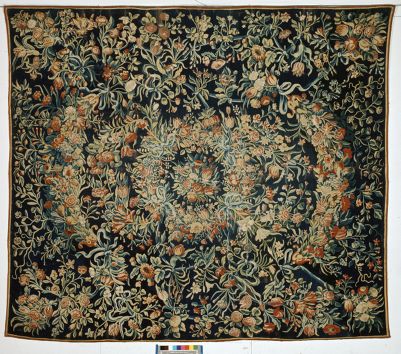

In the Northern Netherlands in the seventeenth century, weavers predominantly worked in a style that paralleled that of the Southern Netherlands. A genre all its own, however, which was mainly executed in Delft and Gouda, were the floral table carpets, which featured different types of sprigs of flowers seemingly strewn about, often accompanied by butterflies or other insects. (Fig. 5) From 1625, a notable number of tapestry series with panoramic landscapes were also produced in the Northern Netherlands. As was also the custom in previous centuries, these tapestries were hung loose in front of the walls, from ceiling to floor, thereby also often covering the doors. An important workshop to make this type of landscape verdure tapestry was that of Maximiliaan van der Gucht and his family in Delft, which was active between about 1640 and 1700.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw several important developments in the field of tapestry in France. Particularly leading among these was the establishment in the second half of the seventeenth century of a system of large royal workshops, such as the Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris, which were able to compete with the production centres in the Southern Netherlands. The Gobelins were primarily concerned with the execution of royal commissions. (Fig. 6) The Manufacture Royale in Beauvais, established around the same time, predominantly supplied tapestries to clients outside the French court. In addition, quite a few landscape verdure tapestries and narrative scenes, mostly of a rather coarse quality, came out of Aubusson and were intended for the trade with a broad clientele.

In the eighteenth century, in France, a change occurred in the way tapestry was viewed. The relationship with painting became ever more profound. This was reflected, among other things, in the application of tapestry borders as imitations of picture frames. Additionally, a new approach to the interior developed in France in the eighteenth century, whereby a new type of tapestry was incorporated in a decorative ensemble. (Fig. 7) The tapestries – usually without decorative borders – were integrated in the wainscoting and combined with matching tapestry upholstery on the furniture. Furthermore, the colours became lighter and featured many pastel hues, just as in rococo paintings. The depictions also became more ethereal and smaller and were often placed in elaborate decorative compositions. Most tapestry for furniture was woven in Beauvais and Aubusson, although the Gobelins did produce some fine ensembles for the French court.

While in previous centuries the Southern Netherlands were at the forefront of developments in the art of tapestry, the eighteenth century saw attention turning towards France. Several large workshops were still active though, especially in Brussels, such as those of Judocus de Vos and the Leyniers and Van der Borcht families. The city of Oudenaarde remained known in particular for the landscape verdure tapestries, often featuring animals. (Fig. 8) In the second half of the eighteenth century only a few tapestry workshops remained operational, and these too closed their doors by the end of that century. Not until the nineteenth century would new weaving workshops emerge, notably in the city of Malines, but the activity was but a pale shadow of the rich history of the previous centuries.

Almost the only workshop to continue its activities in the Northern Netherlands in the eighteenth century was that of Alexander Baert and his family in Amsterdam. (Fig. 9) After 1750 until approximately 1780, mainly smaller items were woven here, such as cushions featuring coats of arms for city councils or water boards.

After the French Revolution (1789) the production of tapestries also ground to a virtual halt in France. However, in the early nineteenth century, under Napoleon, a few workshops, mainly in Beauvais, reopened their doors. They mostly produced decorative tapestries or sometimes narrative scenes after existing, eighteenth century cartoons and tapestry for furniture, for various royal palaces.

Fig. 4

wandtapijtweverij van Jan Raes (II) en Jacques Fobert en Jean Vervoet naar ontwerp van Peter Paul Rubens

Triomf van de eucharistie over het heidendom, 1626-1628

Madrid (stad, Spanje), Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales

Fig. 5

wandtapijtweverij van Anoniem Delft (city) ca. 1650-1675 naar ontwerp van Anoniem ca. 1650-1675

Tafelkleed met bloemkrans, ca. 1650-1675

Den Haag, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, inv./cat.nr. Inv. OW 2-1965, obj. nr. 1011394

Fig. 6

Manufacture des Gobelins naar ontwerp van Charles Le Brun en naar ontwerp van Adam Frans van der Meulen

Koning Lodewijk XIV bezoekt de Manufacture de Gobelins, 1665-1679

Parijs, Mobilier national, inv./cat.nr. GMTT-95-010

Fig. 7

wandtapijtweverij van Léonard Roby naar ontwerp van Marie-François Leclerc

Twee geliefden voor het altaar van Venus, ca. 1782-1790

Doorn (Utrecht), Kasteel Huis Doorn, inv./cat.nr. HuD 00405

Fig. 8

wandtapijtweverij van Jan van Verren (II) of wandtapijtweverij van Frans Willem van Verren naar ontwerp van Augustijn Coppens en naar ontwerp van Adriaen de Grijef

Landschapsverdure met eenden, zwaan, jachthond en bok, ca. 1725-1750

Amersfoort, Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, inv./cat.nr. NK 560

Fig. 9

wandtapijtweverij van Alexander Baert (I) en naar ontwerp van Ludovicus van Schoor en naar ontwerp van Pieter Spierinckx (II)

Europa, ca. 1714-1719

Parijs, Musée du Petit Palais, inv./cat.nr. PPO3514